Sustainability Reconsidered

- Reginald Raye

- Jul 10, 2021

- 7 min read

Updated: Sep 1, 2021

Why Product Design Should Rethink Carbon

Cradle to Cradle, The Story of Stuff, The Upcycle – they are all wrong.

To be clear, we are not ideologically opposed to sustainability in product design. Of course responsible stewardship of Earth’s finite resources is a good idea. But there’s a misalignment between the arguments these books make and the realities of an impactful response to climate change when designing products.

Let’s first examine what is meant, exactly, by sustainability in this context. Common definitions include the repurposing of old materials into new products (upcycling), prioritization of renewable resources as input materials, and switching to manufacturing techniques that are less energy intensive.

These definitions, however, while advancing important considerations, fail to capture the full scope of a product’s environmental impact. A more thorough definition ought to take into account all of the energy flows required to produce something.

Fitting that bill is the concept of emergy, short for embodied energy – the amount of energy consumed in direct and indirect transformations to generate a buyable product or service. We’d argue that an emergy-centric approach to energy accounting is more honest than these other definitions, in that it includes energy inputs from the first mile (e.g. the offshore rig that processed the petroleum for the plastic) to the last (e.g. the truck that brought the widget from the port to the store).

Adding to emergy’s utility is its definability in terms of joules, the standard SI unit for energy, allowing for quantitative comparisons between products.

But look at store shelves through an emergy lens, however, and an alarming picture emerges.

Canvas bags, now mandated in many stores, require farming of pesticide-intensive cotton, chemical treatment in coal-run textile mills, and assembly in sweatshops; fridges made of toxic plastic are Energy Star badged after being shipped across oceans and reassembled in their country of sale. A coop-bought shampoo is made of palm oil sourced from Indonesia's erstwhile rainforest.

Life cycle analysis reveals a canvas bag must be used 20,000 times to achieve emergy parity with a plastic bag

Such ‘greenwashing’ might be more forgivable if it led to a better product. Unfortunately, it does not. Even the most environmentally conscious stores have no choice but to stock generic boxes made of rainforest hardwood, shirts made of Alpaca fleece hand-sheared on denuded mountains, and post-consumer-plastic virtual assistants so bland they would make Dieter Rams (he of “good design is as little design as possible” fame) blush.

A reasonable response to the dismal state of product design – rife with marketing fibs, high environmental costs, and low design quality – might be to fire all product designers and replace them with manufacturing engineers. These engineers are the folks, after all, with the deep manufacturing know-how needed to actually minimize a product's carbon footprint.

We don’t believe this is a good answer. Putting bean counters in charge of design – a practice that, at its best, borders on the spiritual – is a recipe for widgets with all the style and usability of a potato.

Rather, we believe there’s a far better way out of this situation: by ignoring sustainability entirely.

Here’s why.

Consumer goods don’t matter

First and foremost, consumer product manufacturing, in aggregate, doesn’t much matter. Industrial production (only a fraction of which is devoted to consumer goods) accounts for 21% of global greenhouse gas emissions per the US EPA’s latest report. Even if all products were redesigned and all factories were retooled for emergy minimization, it’s unlikely a net emergy reduction of more than 25% would be achievable.

Let us suppose nevertheless that all factories in all countries decided today to do just that, and moreover that a 25% reduction were achieved. This done, industrial production would fall to 16% of total global emissions, bringing consumer product’s emissions in line with one year’s harvest of corn and rice.

Is product greening – by definition, stripping a product to its bones – a proportional response to an improvement of this scale?

If we’re to heed the Pareto Principle, which says that for many outcomes, 80% of consequences come from 20% of the causes, the answer is no. When it comes to moving the needle on emissions, minor sources like consumer products simply don’t have the leverage of major sources like coal plants.

Put another way, might a proportional response entail a shift of focus from stripping down to building out products so beautiful they spark joy?

If we’re to heed our hearts (or look at product usage data) the answer is yes. The click of a shutter on a mid-century camera, the clack of keys on an 80s keyboard, the warm embrace of an Eames chair, all bring inestimable joy to many. Vibrant fandoms attest to their lasting appeal.

Nice to look at, fun to use, and long-lasting – products that put the owner first are often used across decades or even generations

To bastardize a point made in The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, finely made products – those whose rationale is delight – have an aura and artistic authenticity lacking in products whose rationale is austerity.

But for us to get delightful things, product designers first need to be granted the freedom to create with audacity; to design products that engage, enchant, and respond to humanity’s most deep-seated needs.

Green products underdeliver

The user experience (UX) of green products is often poor. Eco-labeled household goods, though more expensive, fail in all-too-familiar ways: detergent that bleaches, trash bags that tear, toilet paper that...

Green products shouldn’t leave a sour taste in your mouth

Setting aside this underdelivering, there’s the problem of overpromising: there’s no such thing as a fully green product. Albeit to a lesser extent than traditional products, green products still require that oil be drilled, forests be cleared, and factories pump out pollutants.

No amount of greening will keep those hydrocarbons in the ground, reforest rainforests-turned-farmland, or suck NOx out of the air. And no amount of carbon arbitrage – whether in the guise of corporate ‘carbon offsets’ or supply chain ‘decarbonization’ – will eliminate the emissions required by production.

Human nature always wins

Beyond poor UX, there’s another reason why ‘green’ products backfire: they need to leverage consumer psychology, not work against it.

For instance, the big-brother-knows best, or even messianic, tone of the sustainability movement can trigger a psychological reactivity response – that is, the tendency to dig in our heels when confronted with something that threatens our behavioral freedom.

Nor should we ignore the way people tend to dispose of goods, green or otherwise: by chucking them in the nearest waste basket. Indeed, having peered into garbage cans the world over, from Tiananmen Square to Harvard Science Center, we’ve found there to be little difference between the contents of the recycling and landfill receptacles.

Green advocates might win more hearts and minds if they were to present sustainable purchasing and disposal as choices worthy of our consideration. It feels better to make a virtuous decision than a forced one, after all.

But this is at odds with the trajectory of sustainability messaging, which becomes ever more strident and, at the same time, divorced from the realities of manufacturing processes and public policy – the boring details that actually determine environmental impact.

The virtue of volume

Short head products (the blockbuster products that predominate over their less-purchased, long tail brethren) are often already low emergy by virtue of their production volume. At scale, emergy per unit can become vanishingly small.

Soda cans, for example, while made of energy-intensive processed metal, are manufactured in purpose-built presses that output hundreds of cans per second. This manufacturing process, refined evolutionarily over decades, consumes very little energy per unit.

Compare this to the biodegradable plastic cup at your local bistro. Manufacturers such as Yasitai are, regrettably, not willing to go on record with the data that would allow for energy accounting. But a back of the envelope calculation (mass per cup of 0.05 kg * PLA plastic of 750 CO2e per kg / batch size of 50 units) suggests energy consumption of 0.75 kg CO2e for a single cup – approximately double that of a metal can (mass per cup of 0.15 kg * aluminum of 1500 CO2e per kg / batch size of 500 units = 0.45 kg CO2e).

‘Eco-friendly’ products notwithstanding, the welcome outcome is that the products we use most often consume the least.

Even if the eco-cup emergy estimate is off by an order of magnitude, it is still comparable to that of a metal can.

Unfortunately, short head products only address about half of our consumption needs. The other, less common products – the long tail – cannot benefit to the same degree from mass production. And at lower volumes, manufacturers have less incentive to introduce process improvements, such as feedstock greening and waste reuse. Many long tail products consequently have higher emergy.

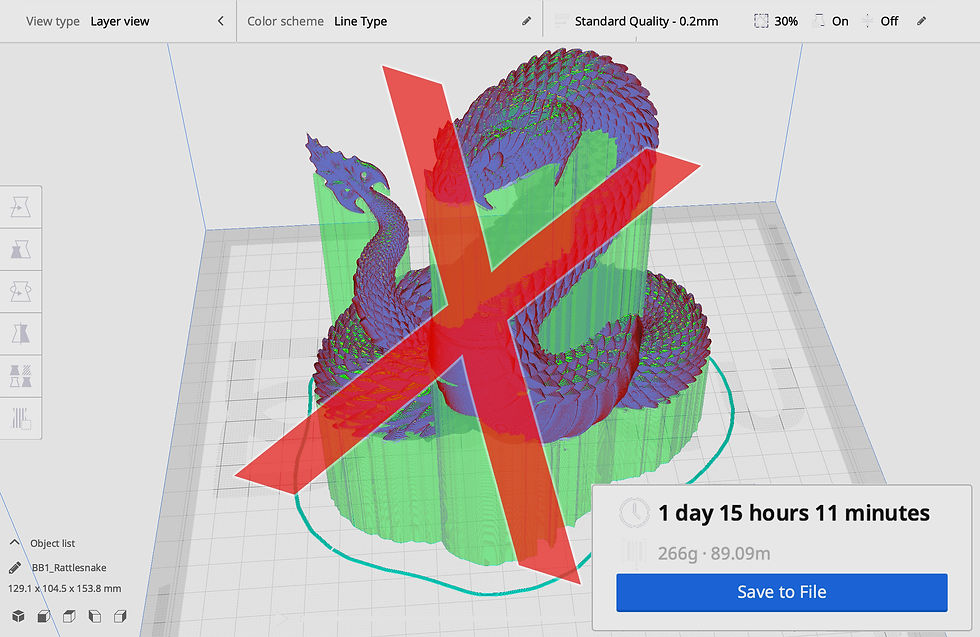

3D printing, a mainstay of the long tail, should be singled out as one of the worst offenders. Contrary to its claims as the bringer of industrial revolution, the majority of 3D printed parts have little functional value, much less aesthetic merit. Though their time on tinkerers’ desks be short, their afterlife is long; PLA filaments take millennia to biodegrade.

Picking the right fight

And a final point. Suppose all consumers everywhere decided today to purchase only what was necessary and to upcycle all their spent products. To be generous, this might yield a lasting 20% dent in consumption, resulting in an approximate 3B ton CO2e annual decrease in emissions.

Source: US EPA summary of IPCC report data

While an emissions reduction of 3B tons per year is not insignificant, it is dwarfed by the impact of electricity generation (13B) and land use (12B). Bearing in mind the Pareto principle, we’d indeed be best served by focusing on short head, high impact culprits like coal plants and logging companies. That might entail lobbying for tighter emission controls, or publicly shaming loggers that fail to adopt sustainable forestry practices.

Big polluters spend billions of dollars each year to spread misinformation about their companies' role in climate change. One goal of these misinformation campaigns is the ‘individualization of responsibility’.

In other words, instead of holding these corporations accountable, we’re encouraged to believe that the best we can do is recycling bottles and rage-tweeting. Or stripping consumer products to their bones.

To this we say – rather than scapegoating product design, let us train our attention on the biggest polluters. Rather than pointing fingers at ourselves, let us train our activism on the governments and corporations with whom lie the power to change course.

If we truly want to address a biosphere in crisis, it’s time to act like it.

Comments